How a life reshaped by motherhood became a blueprint for product craft

On most mornings, the day starts the way it does in many homes across Bucharest: getting a child ready for school, putting together a quick breakfast, and moving through the familiar choreography of family life. Only after this morning rush settles does another world begin, a quieter one where concrete slowly dries on shelves, pigments shift with the light, and a mother steps into the role of maker.

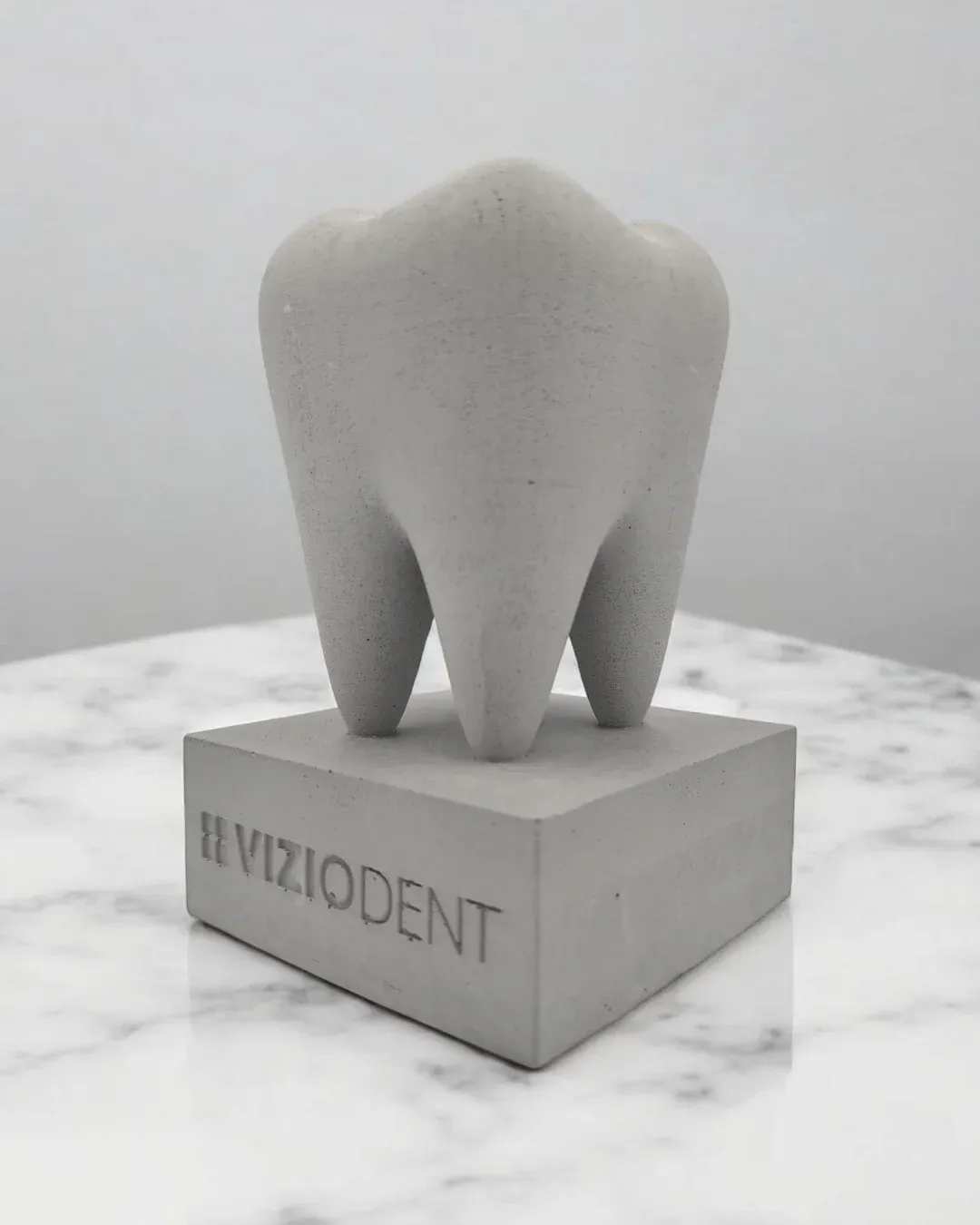

This is the daily rhythm inside Decoristic Atelier, founded by Anca Olaru, mother, wife, and someone who has managed to turn creativity into a steady craft. Her workshop is small and intentional, shaped by years of trial, exhaustion, persistence, and the satisfaction of seeing something take form under your hands. I’ve had the chance to follow this journey closely and, in a small way, contribute to it, which made the evolution of this atelier even more striking from a product perspective.

Her path into this work began when motherhood created a natural pause — the kind of moment that, as she shared in her Forbes interview, reshapes priorities and clarifies what truly matters. For her, clarity became a decision to create a space of her own, to build something that fits the rhythm of her life instead of fighting against it. The atelier didn’t replace her identity; it helped her rebuild it, concrete and strong, quite literally.

How imperfection becomes part of the product’s identity

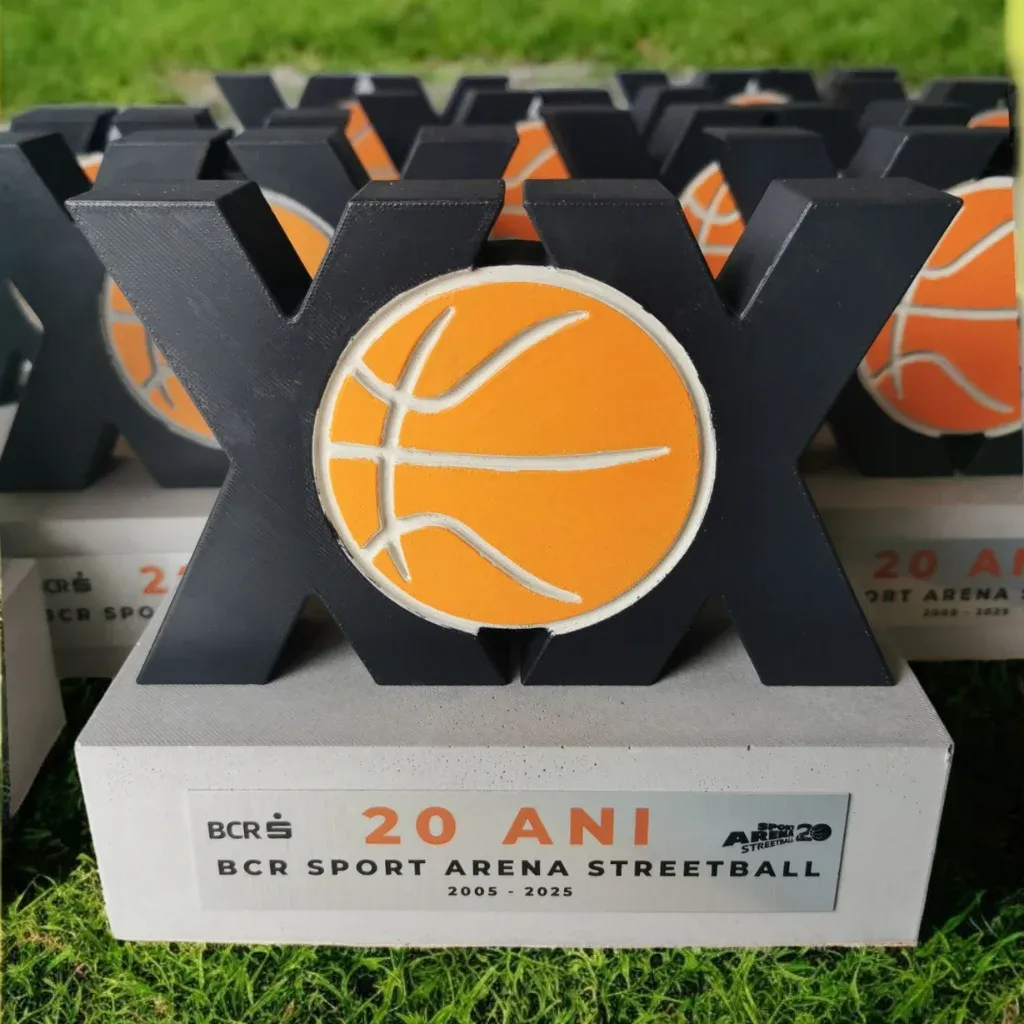

“In the beginning, it was nothing like the high-end concrete trophies I create today for top brands and events across the country. It took a lot of effort to get here. It started with failed experiments, cracks, defective batches, and shelves of unsold pieces. I spent a long time searching and waiting for that one form, that one mix, that one success that would make the effort worth it,” Anca said.

I carefully pick up one of the pieces sitting on a stained table in the corner of the room.

“It’s a prototype that’s giving me a few headaches,” she says with a half-laugh. “The mould isn’t right yet. We need to adjust the 3D print and redo it all again.”

The weight feels honest in my hand. The texture is irregular in an intentional way rather than accidental. Every piece carries small traces of the person who shaped it. These aren’t flaws, they’re the quiet signatures of real work, done by hand, within the limits of real life.

This is how you sense the difference between something produced and something made.

We speak often about reducing friction, eliminating variation, and smoothing every edge. But the physical world doesn’t always cooperate, and neither does daily life. In this workshop, imperfections are not errors; they are a natural part of the process. They remind us that products rarely emerge from ideal conditions. More often, they emerge from people balancing responsibility, time, limits, and a genuine desire to create something meaningful.

Decoristic Atelier

The balanced ecosystem in one pair of hands

Decoristic Atelier is, in essence, a compressed product ecosystem. Anca is the designer, the material researcher, the operator, the quality controller, the packer, and the one who answers client messages in the evenings. In companies, these roles are separated by departments and processes. In her workshop, they live within the same day, sometimes at the same moment.

What makes this even more striking is that she had to learn and master many of these skills on her own. Her studies in chemistry and business administration helped, but most of the craft, the processes, and the operational know-how came through self-teaching, experimentation, and the patience to stay with a task until it became second nature.

It’s a reminder that when someone sees and shapes the entire lifecycle of a product, the outcome naturally reflects their values, not just their skills.

Working with concrete reinforces this reality. It’s a material that doesn’t respond well to haste. It needs time, the right temperature, the right humidity, and a willingness to adapt. It teaches patience and rewards consistency. There are no shortcuts and no automation that can replace understanding the material with your hands. What looks simple from the outside is a quietly complex system held together by attention rather than machinery.

And then comes the question of scale, a question that hovers over any small creative business. Growth can bring opportunity, but it can also dilute the qualities that made the work meaningful in the first place. For an atelier, scaling means standardising, delegating, and speeding up. It often means losing a bit of the closeness between maker and product. Not every craft benefits from becoming bigger, and not every product becomes better just because it becomes more efficient. Sometimes, maintaining identity is more important than increasing volume.

What I find most compelling in this workshop is the kind of knowledge that doesn’t appear in documents or dashboards. Her hands and eyes know when the mixture is right, when a mould will release cleanly, and how long a surface needs before it can be handled. This is experience-driven knowledge, the kind that accumulates through repetition and genuine engagement. In many industries, this form of tacit expertise is undervalued, yet it often explains why some products succeed despite imperfect systems and why others fail despite careful planning.

The weight of meaning: When products become symbols, not objects

There is also something worth noting about the purpose of the objects produced here. A concrete trophy isn’t functional in the usual sense. It doesn’t solve a problem or perform a task. It represents something more: appreciation, recognition, a moment that matters to someone. Meaning is part of the product, and meaning is very hard to mass-produce.

A product becomes a symbol the moment it carries a story, not just a function.

This atelier shows a side of product development that we rarely talk about directly: that products are shaped not only by markets and processes, but by the lives of the people who make them, by their time, their constraints, their hopes, and their everyday decisions. It reminds us that real products, in any industry, are the result of human judgment rather than perfect systems.

When I hold one of these pieces, I’m reminded that the story of a product often begins long before the material takes shape. It begins in the life behind it, in the decision to build a balanced, sustainable craft within the flow of family life. The workshop is small, but its lessons reach far: constraints create focus, care creates identity, and the human side of work is not a detail, it is the centre.

And in a broader sense, that is the paradox: sometimes the clearest truth about how products are built emerges not in boardrooms or sprint reviews, but in quiet workshops where things are made hands-on and by intention, one iteration at a time.